The Nike sync is currently down. As of Sept 28th, new runs are no longer flowing through the pathways we use to retrieve your data. We’re not an official partner of Nike, and so we don’t have any recourse, but to wait and hope that they fix something.

This turn of events is all the more painful because I’ve just spent over a month working to make the Nike import bulletproof. We have a fair number of Nike users on Smashrun and, for many people, the data we’ve retrieved has become the sole existing record of those runs. It pained me to see the frequent problems and errors. So, I rolled up my sleeves and attacked the issue wholeheartedly. I invested an embarrassing amount of time in the task.

There are currently dozens of different sources for the runs that end up on Nike’s site: the watch, the footpod, the iPhone and Android apps, runs sent from Tom Tom, runs sent from Garmin, the Apple Watch, and even connected treadmills. Each of these sources have unique data signatures – the data is registered in the same fields but with different meanings. This means that each source must be handled differently. And, of course, these sources have also changed historically as old bugs were fixed, and new ones were introduced. In short, it was a fool’s errand, the deepest and darkest morass.

After spending a month in the weeds, building a matrix of kludges based on the different versions and sources, I can only describe the way the data is stored like this… Imagine you wrote a love poem, and faxed it to a machine running out of ink, somewhere in Glasgow. Someone picks up the printout, stuffs it in their pocket and carries it through a rainstorm to the nearest pub. Once there he hands it to the first person he finds who happens to have this terrible cold, and they uncrumple the soaking wet fax, with it’s smeared ink, and they read it in their thick Scottish brogue over a bad Skype connection to someone who’s hard of hearing. It’s kind of like that.

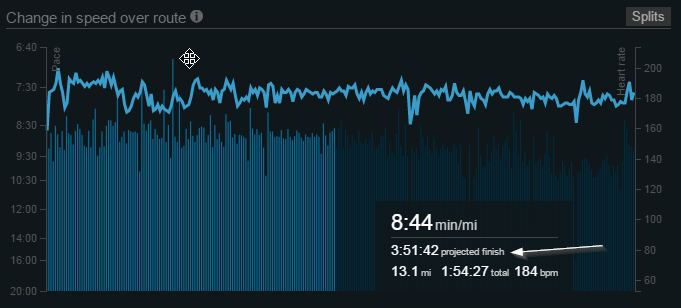

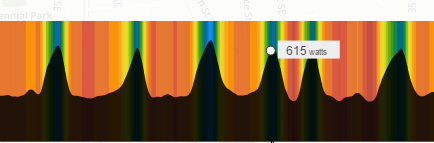

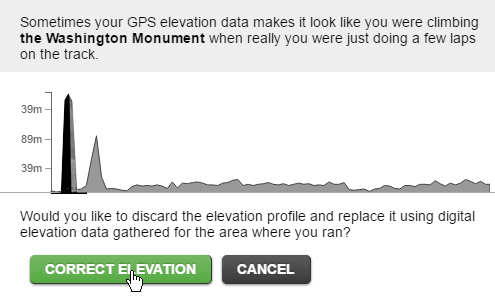

Ok, well, it’s not exactly like that. From the 1,000 foot view that Nike’s site gives you, everything appears to be in order. Yes, the graph goes up and the graph goes down, and indeed, it does change colors. Yes, there’s a map that shows pretty much where you ran. Yes, there are splits. But, no… those splits can’t be backed out of the raw data. And if you calculate the distance based on the GPS points, it won’t match the distance you’ve been given for that run. And the bits on the graph where it’s green don’t always match the places where you ran fast.

In practice, the data isn’t there. Not really. What you see on Smashrun, I think, is the best that can be done. And, for some device/software version combinations, the data should be pretty good now. But, looking back at it, no programmer who wasn’t also the founder of the company, would ever have been given the latitude to sink so many hours into this project. To be honest, it was as much a crusade as anything else. Runs are personal, the record of the run is personal, and that data is yours – you should be able to have access to it.

Which brings me back to the current situation. Nike usually stages runs from the main site to their API. But, at present, that’s no longer happening. I suspect that at some point, someone may notice and reboot a process somewhere and get things back on track, or the choice may be deliberate in which case the sync will be broken for good. I highly recommend supporting companies that believe in data portability.

—

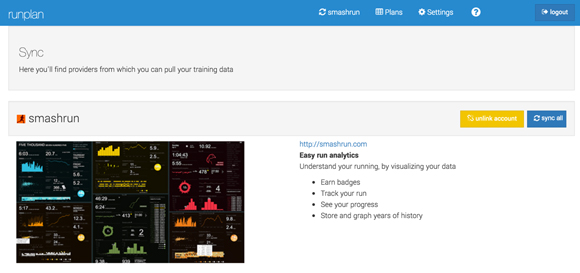

If you’re using an iPhone, iSmoothrun has a great app as well as a standalone Apple Watch app that exports to Smashrun (and many other sites).

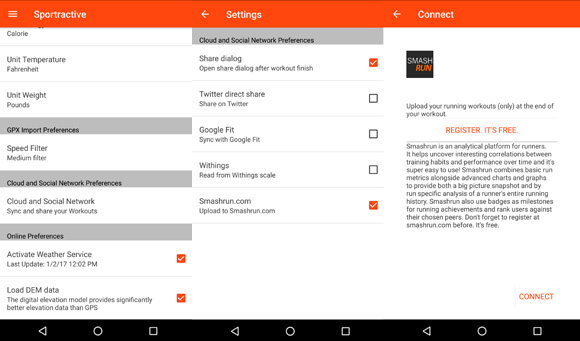

If you’re using an Android phone then Sportractive, Caledos Runner, and Ghostracer all export directly to Smashrun (as well as other sites).